Exploring Bo-Kaap: History, Culture and Ethical Travel in Cape Town

- valeriehuggins0

- Nov 29, 2025

- 3 min read

During my trip to South Africa, I went to vsist the district of Bo-Kaap, tempted by the prospect of some great photos of its iconic colourful houses. It is one of Cape Town’s most photographed and culturally rich neighbourhoods, famous for its brightly painted houses and deep Cape Malay heritage. But beyond the colours lies a history shaped by colonialism, slavery, Apartheid, and a community determined to preserve its identity. Visiting Bo-Kaap can be both fascinating and challenging—especially for travellers who want to engage respectfully.

Before I went, I did some research on the history. Bo-Kaap is the oldest residential area in Cape Town, dating back to the 1760s, when the Dutch built and leased homes to enslaved people and exiles from Indonesia and Malaysia. After gaining their freedom, many residents painted their houses in bright colours as an expression of joy and independence. This tradition continues today and has become one of the most recognisable aspects of the neighbourhood. The district’s character strengthened further during Apartheid, when the Group Areas Act of 1950 forced Bo-Kaap to become an exclusively Muslim residential area. People of other ethnicities and religions were made to leave, reinforcing a strong Cape Malay identity. The neighbourhood is also home to South Africa’s oldest mosque, built in 1794, yet seems to be surrounded by modern development indicated by the flock of yellow cranes:

In recent years, Bo-Kaap has also become one of Cape Town’s busiest tourist attractions. Buses drop visitors off to take a few snaps before heading on. I found the streets congested with traffic or dominated by large tour groups, pointing cameras into people's homes. There is little time for them to spend in the local shops. I bought a couple of fridge magnets—hardly a major contribution, but more than many leave behind. I was also bothered by the visible economic hardship evident by the young women sitting on the pavement edges with their young children asking for aid.

I arrived in Bo-Kaap hoping to photograph abstract angles and striking facades. But almost immediately, I felt the familiar discomfort of photographing in a lived community. My reluctance to photograph people without consent already limits much of my street work. Here, it felt especially intrusive. So I played around with some ICM on my phone to diffuse and diffract the images:

Was I any different from the rapid-fire tour groups collecting images like trophies? At the very least, I wanted to understand the history before lifting my camera—and to recognise that Bo-Kaap is not simply a colourful backdrop; it is home to a community.

I recalled the advice of photographer Alex Kilbee: “Look for the adjective, not the noun.” Don’t just photograph a tree—photograph its treeness. That idea guided me as I walked through Bo-Kaap. Instead of chasing the obvious 'postcard' images, I tried to look deeper. The colours represent freedom to the Bo-Kaapers, so I looked for joyful juxtapositions of colour:

This is a thriving community behind the facades. I tried to represent this through finding living things, such as the trees and the potted plants, with the shadows representing the past:

I hoped that by focussing on the small details, as well as putting some thought into the process of image making, I was not just grabbing snapshots.

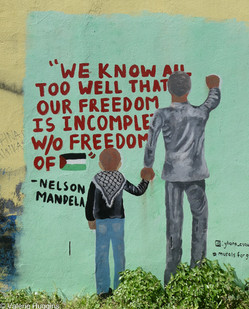

I was surprised, though perhaps I shouldn't have been, by the way the walls are used as a public canvas to convey resistance and humanitarian messages:

In line with my ethics about photographing people, I deliberately avoided photographing the mothers sitting on corners with their toddlers close beside them., even in return for a donation. What would I have been able to do the images anyway? Photographing them felt exploitative, no matter how carefully framed.

I discovered that Bo-Kaap is vibrant, complex, and deeply human. Its colours are only the beginning of the story. Walking its streets reminded me that travel—and especially travel photography—isn’t just about what we see. It’s about how we choose to look.

To “see” Bo-Kaap is to acknowledge its beauty and its struggle—and to move through it with respect, curiosity, and humility.

Comments